I’ve just finished reading The Cold Dish, the first story in Craig Johnson‘s Longmire series.

I haven’t seen the television adaptation, so don’t know how closely it mirrors the pacing and depth of the books. I was surprised at how intimate the internal dialogue of the protagonist Sheriff was, with Walt Longmire revealing his doubts and insecurities. Baring his throat made me bond with him as a character.

It’s vital to let the reader in—if you don’t share, why should they care? (That sounds like an advertising slogan!) A friendship grows not because someone is always strong, but because we love them despite their weaknesses. The same should be true of your fictional characters.

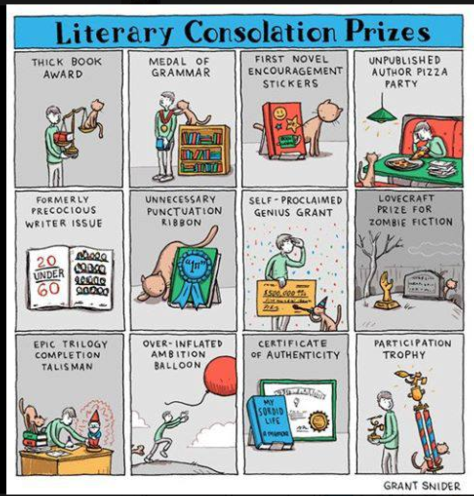

Happy to bare her throat

Infallibility might be attractive in superheroes, but in portraying the humanity of ordinary folk their missteps are more endearing than if they’re constantly triumphant.

But, what of giving the reader a peek at your character? When writing what you know, it’s likely that personal emotions will seep into the page. Fans of your writing will smile knowingly, attributing a scene featuring a quarrelling couple to your own marital breakdown. Such things are inevitable, especially if you write about sex.

In my own stories, poems and song lyrics I’ve tackled bereavement, divorce, loneliness, depression, suicide attempts, poverty, near-death experiences and acts of violence, all of which I’ve known. The reactions of my characters to these events isn’t the same as mine, but certainly informs them. Does it make my writing realistic and engrossing because it feels true? I don’t know, but I believe powers of imagination can only take a writer so far.

I’m currently reading two well-reviewed books about alternative ways of living. Being autobiographical, they offer close insights into the thinking of a disenfranchised woman living in a shed and a disillusioned man who decides to exist without technology.

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/jul/06/homesick-catrina-davies-review

Catrina Davies and Mark Boyle’s honesty is refreshing. They have no front about who they are, no deception about their circumstances. They bare their throats, say what’s in their hearts and get on with surviving by stumbling through different options. Their candour and vulnerability will affect how I portray my characters.

Being a know-it-all is a good way of losing friends and influence. I once met a young man, a computer whizz who had several IT patents to his name. At 17-years-old, he had more arrogance than discretion when boasting about computers. But, growing up in a moorland village, he wasn’t socially confident, and was nervous about going away to a city university. I advised him to occasionally admit to confusion about things, requesting help to encourage bonds with fellow students. I saw him a couple of years later, and he thanked me, for my tactic had worked!

https://curiosity.com/topics/people-who-can-admit-what-they-dont-know-tend-to-know-more-curiosity/

The title character of my Cornish Detective series is going to be forced into showing his frailty in the next story, no longer able to rely on the support offered by his status as a copper, because he’s fallen in love with a woman who may have a criminal past.

How do your characters bare their throats?

Do you have any favourite fictional protagonists whose vulnerability created empathy?

I bonded with Lyra Belacqua and Will Parry from Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy.

I worry about what they’re up to, even when not reading the stories!