I’ve never had any training in how to type, so am what is known as a ‘hunt and pecker’…which sounds rather rude, now I think about it!

My primitive technique entails using one finger on each hand to hit the keys. I think that other fingers may sometimes get involved, but only when I’m in full flow. I’m of an age to have once used old fashioned mechanical typewriters, which was an ordeal owing to the pressure needed to depress a key. I dare say that writers of old had stronger fingers than modern authors, who are spoilt by soft touch computer keyboards.

Typewriters were so heavy! I was given a Smith Corona desktop cast iron model, that weighed 35 pounds. It felt more like a potential bludgeon than a tool to help me write.

As is the way with obsolete technology, typewriters have become collectable. Tom Hanks, of all people, recently published a collection of short stories called Uncommon Type, with each story being written on one of his favourite typewriters.

Will Self is also a fan of typewriters:

“Writing on a manual makes you slower in a good way, I think…You don’t revise as much, you just think more, because you know you’re going to have to retype the entire thing. Which is a big stop on just slapping anything down and playing with it.”

I briefly knew a secretary, who’d been trained to touch type, and her hands were a blur. She averaged 75 words a minute, and eerily, knew exactly where she’d made a mistake when she finished typing.

When I’m in the groove, I can churn out 40 words a minute, with only a few mistakes. Looking at the keyboard slows me down, though I’m always surprised that my fingers have any sense of where the correct keys are when I concentrate on the screen.

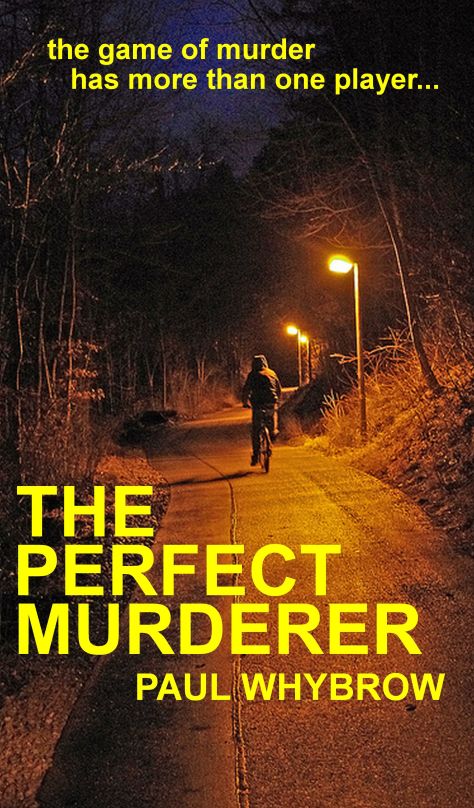

My writing method starts with making copious notes on my laptop about everything from forensic details to characters’ motivations, to words and phrases and conversation snippets that I want to use. I don’t compose a formal plan of where the plot will be going, preferring a pantser approach by letting my characters’ actions propel the action. However, I always know what the climax of the story will be, including the mood I’m trying to achieve for the end of the action.

I write directly to the screen. Any speed I have in typing was slowed when writing my last novel, as I changed technique by staying on one chapter for several days, backtracking and reworking.

I’ve known a couple of authors who write the first draft in longhand, using their lucky pen, before typing it out on a mechanical typewriter. They spend much time scanning and printing out their novels. Strangely, both of them own computers but don’t like using them for creative writing. They like the racket that an old metal typewriter makes, and they’re proficient at typing, making few mistakes…which might be a benefit of this way of writing, as errors are harder to correct.

How do you write your stories?

Are you a trained typist, or is one finger on each hand blunted and calloused?