I’d like to return to the adventures of an American Civil War veteran. I’ve written two novellas about Art Palmer negotiating his way through the war-torn Deep South in the era of Reconstruction, as he makes for his sister’s plantation in Georgia. I’d like to know what happens to him. I’ll find out in early 2020.

One project that’s firmly on the back burner is a vaporous notion I had for a literary novel about communication, identity and dating in an age where we all surveilled online and in the street with CCTV. I intended that to be my first novel, after writing twenty short stories and novellas and 460 poems in 2013-2014. Then, I saw advice on several writing gurus’ sites that placing a literary novel written by a debut author was the most difficult of sells for an agent. It was better to stick to genre writing, hence I chose Crime which allows me to write about anything.

I’ll probably never get around to penning my magnum opus about relationships in the 21st-century where we can spy on one another and where we’re spied on by Big Brother, but plenty of famous authors never completed their final manuscripts:

10 Famous Authors and Their Unfinished Manuscripts

What stories are on your back burner?

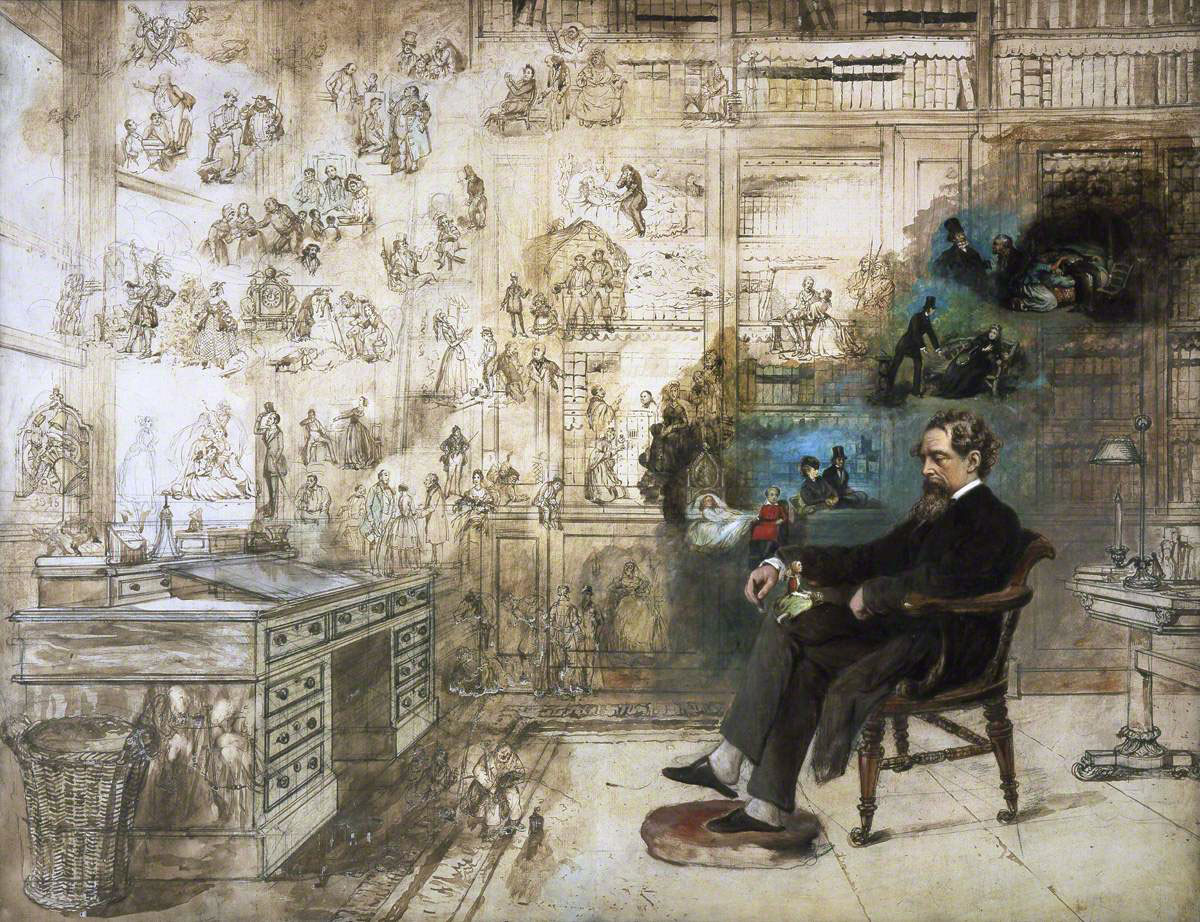

This unfinished painting of Charles Dickens imagining his characters depicts how we’re haunted by writing projects. The painting Dickens’ Dream was begun on the death of Dickens in 1870 but hadn’t been completed by the painter Robert William Buss when he died in 1875.

, more because the stories are in me and insist on coming out. But, thinking of qualities shown by a potential mate, her being a writer would be desirable to me. At least I’d know something of why she was behaving in that strange way from my own experience!

, more because the stories are in me and insist on coming out. But, thinking of qualities shown by a potential mate, her being a writer would be desirable to me. At least I’d know something of why she was behaving in that strange way from my own experience!